Print This Post

Print This Post

And God said to Moshe, ‘Come to Pharaoh…’, Pharaoh is to be understood as the Void (halal ha-panui).

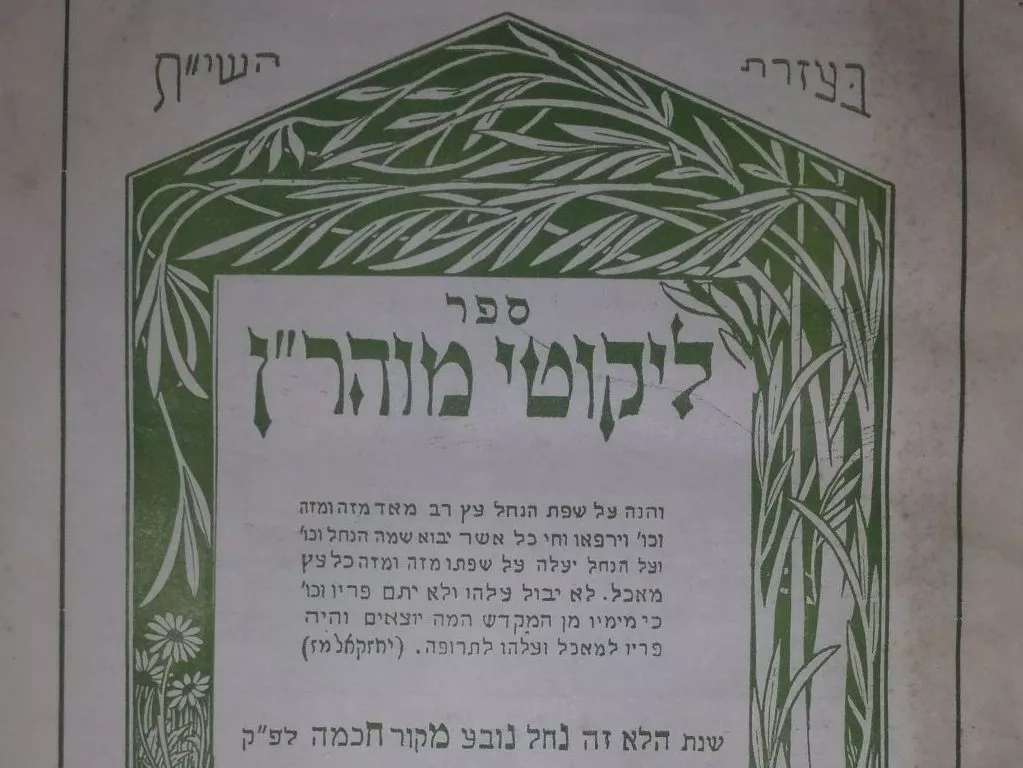

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov, Likkutei Moharan 64

Most of what we experience in our day to day lives fails to really stay with us. We may remember events for a stretch, but eventually the tide comes in and they wash away like sandcastles splashed by the waves. There are, however, significant moments that inevitably stand out. Something about them grants them a sense of permanence, and no matter how many years have passed, we remember where we were when they occurred and more importantly, how they made us feel.

For me, the first time I read the writings of Rebbe Nachman of Breslov was one of those moments. Up until then, I had an interest in Chassidut, but had never really explored his thought. To be honest, I wasn’t sure if Rebbe Nachman was ‘serious’ enough for me. The way his teachings are often presented in the popular consciousness caused me to assume that his writings were only about the importance of emunah peshuta, simple faith. It was only after the urgings of my chavruta at the time, that I finally felt compelled to open up Likkutei Moharan, Rebbe Nachman’s most important work. My chavruta insisted to me that there was much more there than I had imagined and that knowing me, the best place to start was Torah 64, a drasha on Parshat Bo. He concluded by saying that I would thank him afterwards, and he was right.

I first read Torah 64 from a weathered copy of Likkutei Moharan that I found tucked away in the beit midrash I studied in at the time. It was in the afternoon after mincha at a time during the day when I usually struggled to regain my focus after a long morning of learning. I opened up to the drasha, and immediately found myself roused from my post lunch drowsiness by what I read.

What struck me first was Rebbe Nachman’s language. In Kabbalah, language is understood to both reveal and conceal. It gives form to thought and can convey clear meaning, yet at the same time, it hints to so much more than can be expressed in simple words. Rebbe Nachman’s teachings are a classic example of this. He writes about profound ideas in an accessible style, yet one is constantly aware that he points to religious truths that can take a lifetime to fully comprehend.

In this particular Torah, Rebbe Nachman grapples with a contradiction at the heart of all Chassidic thought. On the one hand, ‘melo kol haaretz kevodo, the world is filled with God’s glory’ and creation is saturated with the divine. The problem, however, is that while this may be true in some ideal fashion, most of us do not experience the world this way. We may feel God’s closeness at times, but most of our lives are spent immersed in a physical reality that appears to exist at a near infinite distance from an all-powerful loving God. In the attempt to explain the contradiction, Rabbi Nachman states that in fact, an infinite God has no choice but to engage in tzimtzum, self-contraction, in order to make a space for creation. However, the act of tzimtum has a radical consequence. It creates a Void (halal ha-panui) that is empty of God. Paradoxically, creation exists both in the Void absent of God and yet at the same time, must be fully part of the divine, for how can anything exist separate and apart from God?

The Void may be an inevitable outcome of creation but it is not without its consequences from which none of us can escape. Many of the challenges we face in life push us nearly to our limit, but over time we come to learn that they do indeed have answers. If we commit ourselves fully to the struggle, we can in fact find our way through them. It may not come easily, but there are answers to be had, if we are willing to work hard enough. There are, however, questions of a different type that which come from the Void, questions that emerge from a place of God’s absence. These questions are of a different quality. One can struggle with them and fight them with all of one’s energy, but even after many years, one will discover that no true progress has been made. When confronting them, the Void becomes like a black hole, whose gravitational pull cannot be overcome after being sucked inside. In describing the questions that come from the Void, Rebbe Nachman offers a distressing yet profound truth. Some questions have no answers. As a result, there are many souls, too many in fact, which find themselves trapped in the Void.

From the time that I first started learning seriously in yeshiva, I had found myself struggling with questions of divine justice. How could a righteous God, who is the embodiment of love and compassion, create a world with so much pain and suffering? We can attempt to paper over this question, but eventually, the weight of the questions that come from the Void will burst through, and in the process, we inevitably catch a glimpse of the Void and feel its pull even stronger.

If the Torah were to end here, Rebbe Nachman would justly earn the title of ‘Tortured Master.’ However, he is unwilling to let the questions of the Void be the final word on human existence. While we may not be able to escape the Void on our own, others can help us. Rebbe Nachman speaks of the tsaddik who can enter into the Void and show us the way out. The tsaddik achieves this through the singing of a niggun, a wordless song. The reason for this is simple – words are of no help in the Void, because it is a place where meaning cannot be found.

Rebbe Nachman perceives this dynamic in the story of the Exodus, where the tsaddik is none other than Moshe Rabbeinu and the Void is the heaviness of Pharaoh’s heart. Though the Jewish people have become enslaved to the Void, Moshe is perhaps the one Jew who has retained his freedom and he must do the unthinkable. He must come to Pharaoh, descend into the Void, with the hope of leading the Jewish people back out.

I have often asked myself, what was the niggun that Moshe sang to free the Jewish people from the Void? What did it sound like? Perhaps Moshe sang the tune the he would eventually use for Shirat HaYam, the Song of the Sea, when the Jewish people finally achieve their freedom. However, I have come to think that there is another possibility. Maybe the niggun is not just one song. Maybe it’s more like jazz; improvisational, creative, never sounding the same way twice and pulsating with an energy that grabs hold of you and doesn’t easily let go. I would have to believe that its melody cannot easily be described or put it into words. But whatever it sounds like, it is the only thing that can cut through the deafening silence of the Void.

Whether we like to admit it or not, so much of our religious lives are deeply conventional. Even in the moments when we are faced with challenges that cry out for depth and authenticity, we are rarely surprised by the Torah that is offered to us. In a way this is understandable. We demand certain conventions even if they don’t satisfy our deepest needs, because they provide us with a sense of stability and security. But these cannot help you escape from the Void when we feel ourselves crushed under its weight. To do that we need something that defies the norm and offers us something that is truly new and different. We need a niggun that snaps us out of our despondency and points to deep meaning yet to be discovered. For me, the writings of Rebbe Nachman serve as that niggun, and when I approach Parshat Bo, I cannot help but hear it getting a little louder.